Introduction to the Indigenous Taiwanese Peoples

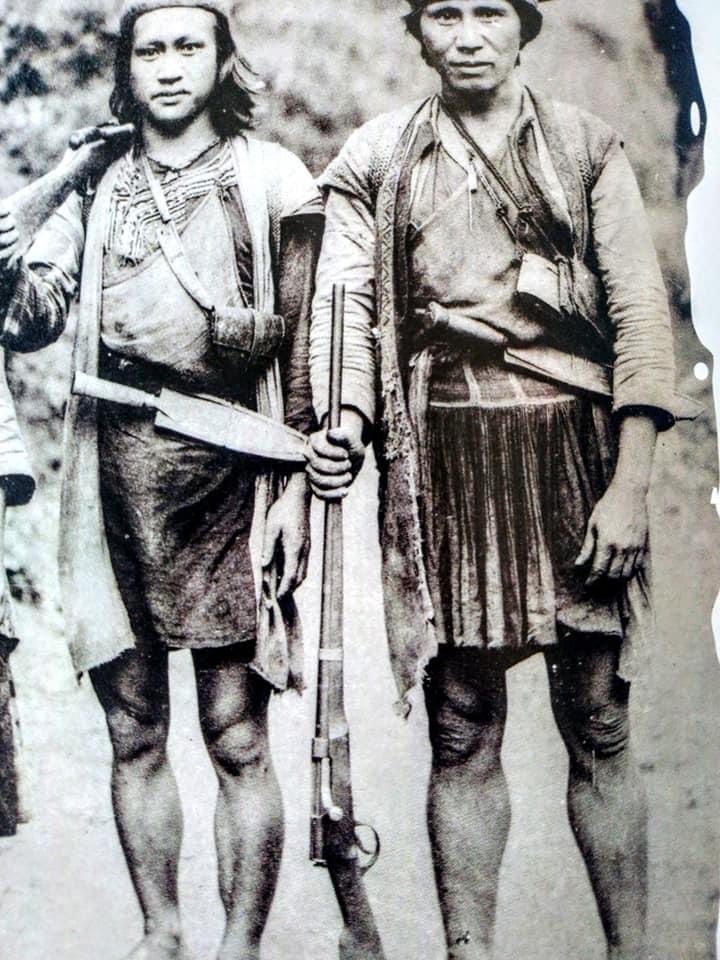

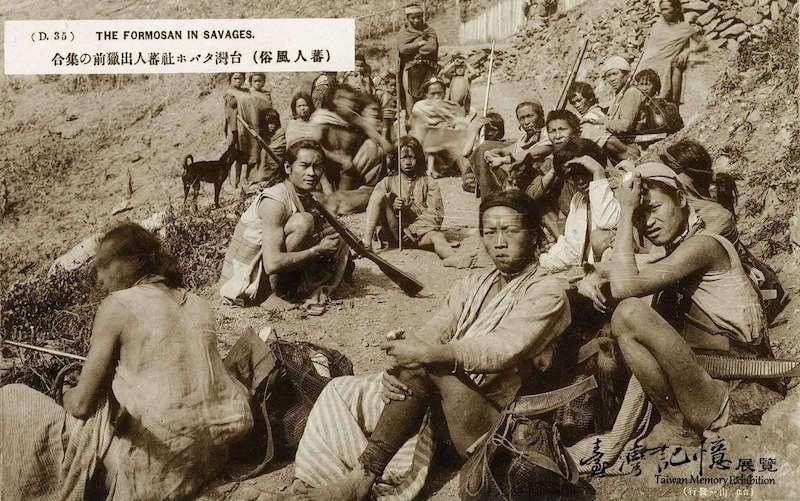

Taiwan, an island just 81 miles off the coast of China, is home to 23 million people, mostly speaking a form of Chinese, observing Chinese customs, and upholding Chinese institutions. Yet, before the waves of Chinese migration and the imperial escapades of foreign colonial powers, Taiwan was home to some of the first Austronesian speaking peoples. These people, the Indigenous Taiwanese, not only retained unique and archaic elements due to geographical barriers and thousands of years of relative isolation, but also differentiated into distinctive language, cultural, and ethnic groups. At least 26 distinct groups are known to have existed, and as of 2025, 16 tribes are officially recognized by the Taiwanese Government, with a few others on the way. Academic consensus suggests that Taiwan was likely the first in a series of stepping stones for the spread of the Austronesian peoples to eventually reach the ends of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Together, the Indigenous Taiwanese languages comprise 9 of the 10 subgroups of the Austronesian language family.

However, as a result of Dutch, Chinese, and later, Japanese occupation, the Indigenous Taiwanese have suffered displacement, population loss, and cultural erosion. During Japanese colonial rule, many indigenous villages were forcefully relocated to the lowlands both for easier control and partly to mitigate natural disasters more common in the highlands such as landslides. Starting with the Japanese and continuing under martial law imposed by the KMT, local and Indigenous languages and culture were actively suppressed. Entire generations grew up not being allowed to speak their languages and practice their culture openly. While at risk of disappearing, the unique linguistic and cultural characteristics survived through the efforts of cultural torchbearers. With the help of academic study, ethno-ecological tourism, adoption of enlightened attitudes by the government, and programs aimed at cooperating with and preserving indigenous culture, Taiwan has experienced a revival of indigenous culture and increased recognition of its importance in the world.

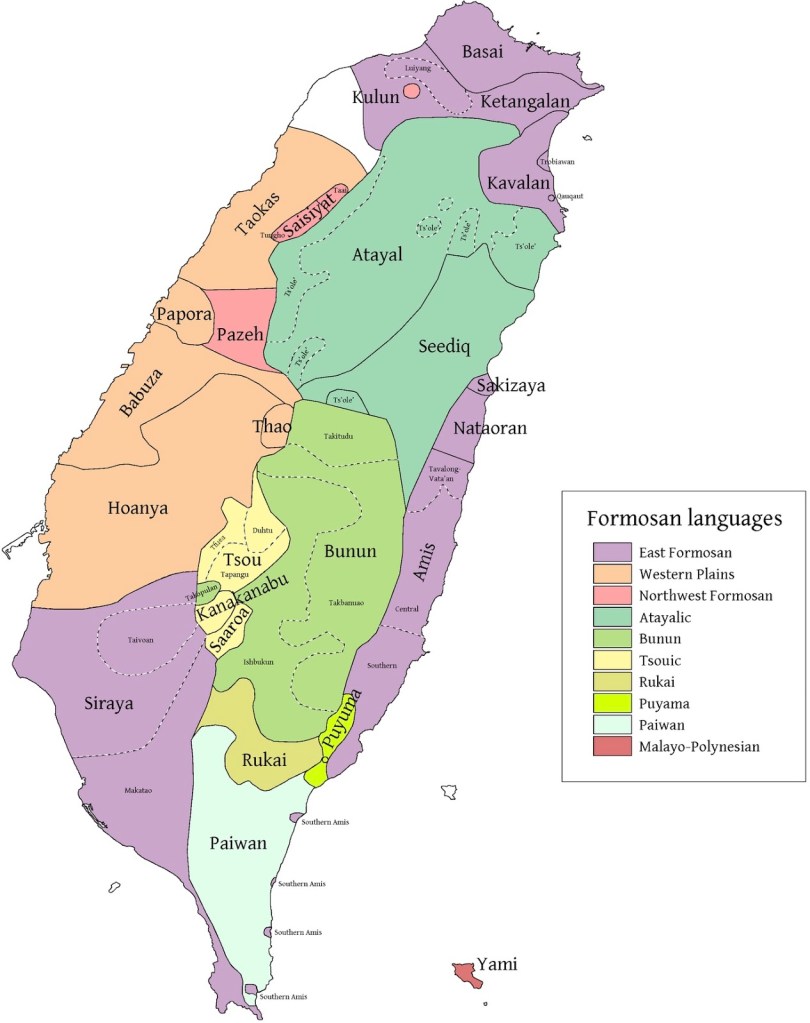

Traditional Territories of Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples

The many groups of Indigenous Taiwanese peoples can be distinguished by distinct cultural features, linguistic relations, and shared histories. While the Taiwanese government has officially recognized 16 distinct tribal groups, these categorizations do not necessarily reflect the local realities of daily life in the past and present. Rather, villages have often organized themselves in a variety of ways, ranging from clans, tribal confederations, to semi-feudal kingdoms that often transcend cultural and linguistic differences.

Northern Mountains

The mountains of Northern Taiwan that encompass Taipei, Taoyuan, Miaoli, Hsinchu, Yilan, and the northern stretches of Hualien, Nantou, and Taichung are home to the Atayal, Seediq, and Truku peoples. Once all classified as the Atayal, they share close cultural and linguistic ties, with their languages at times nearly mutually intelligible.

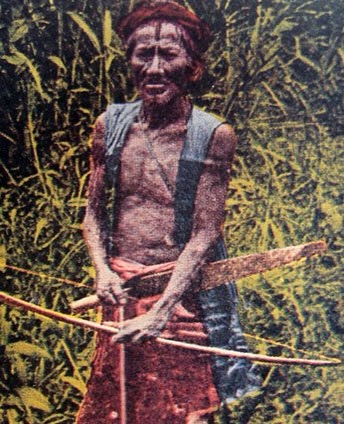

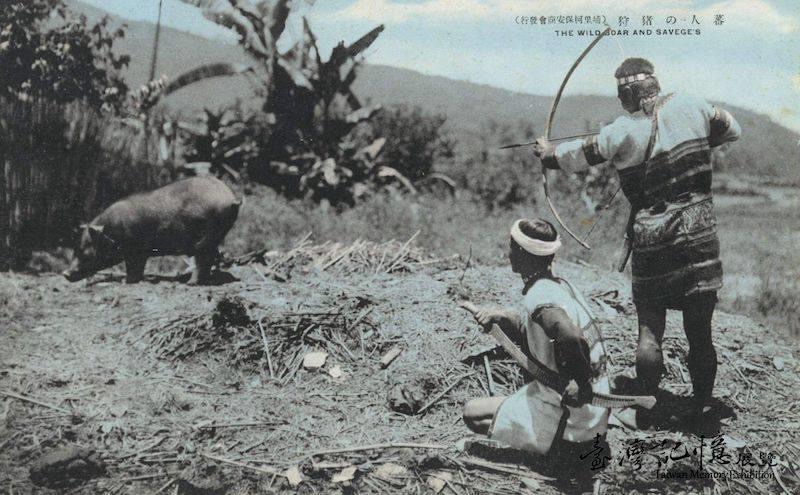

The Atayal occupy the largest geographical area of any indigenous group in Taiwan, and are thought to have originated from the western side of the Central mountains in the upper reaches of the Zhuoshui river valley before migrating east and north. As highlanders, they inhabit clearings halfway up steep mountain valleys inaccessible to most others. The Atayal lived as subsistence farmers, practicing slash and burn agriculture along the mountain slopes. Men were also expected to be accomplished hunters, trappers, and spear fishermen and survive in the woods with little more than their knife and some salt. Women were expected to learn to weave from a young age and process the stems of the ramie plant into usable thread. The traditional knowledge, social customs, and morality that each person was required to know was collectively called Gaga/Gaya by the Atayal, Seediq, and Truku. A unique aspect of Gaga was the Ptasan, or facial tattoos, which served as a coming of age ritual and as well as tribal identification. They were given to each man when he took a head or managed a successful hunt and to women when they mastered the art of weaving. Another such aspect is the belief in the Utux, or ancestral spirits, which are thought to watch over them from the spirit world or pass judgement and punish those who have violated Gaga. The Atayal, Seediq, and Truku believed that after death, the Utux would only let the worthy, such as those that lived according to Gaga and possess facial tattoos to cross the rainbow bridge into the spirit realm. While the Atayal were not usually politically organized beyond large clans that encompassed multiple villages, when cooperation was necessary, clans would coalesce to form larger alliances, such as during the Tapung/Lidongshan(李崠山) incident(throughout 1910s), where the clans of Mkgogan in Taoyuan, and the Mrqwang and Mknazi in Hsinchu cooperated to fight Japanese encroachment.

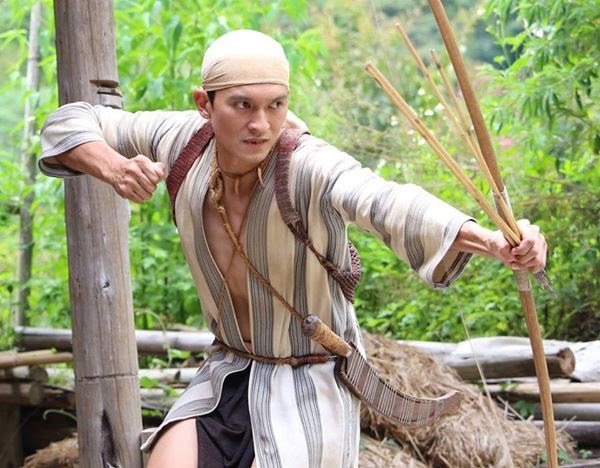

One subgroup, the Seediq, straddles the eastern and western sides of the central mountains. The Seediq are well known for their involvement in the 1930 Wushe/Musha rebellion, in which the Tkdaya clan of the Seediq launched one of the last major uprisings against Colonial Japanese rule in Taiwan. Prior to the attack, the Japanese had suppressed traditional activities such as weaving and tattooing and pressed the men into labor. Japanese police officers had also regularly harassed the villages, which culminated when, during the wedding of Daho Mona, son of chief Mona Rudao, a Japanese officer had refused a symbolic offering of wine from Daho Mona and assaulted him. Following the conflict, Mona Rudao led around 300 Seediq warriors in storming the local police stations for weapons and ammunition and attacked a local school, where many of the local Japanese had congregated for sports day. The ensuing struggle saw the deployment of the Imperial Japanese army and allied Seediq Toda and Truku warriors to fight the rebelling Tkdaya. Due to encirclement and starvation, many Seediq, including women and children opted to commit suicide rather than submit to the Japanese. While the remaining Seediq eventually surrendered to Japanese forces, the uprising of pacified natives, of which the Tkdaya were considered a shining example, forced the Japanese government to reconsider their attitudes towards the Indigenous Taiwanese, which was reflected in the redesignation of Indigenous Taiwanese peoples from “Raw savages” to Takasago(Highland natives). The events were depicted in the 2011 film Seediq Bale: Warriors of the Rainbow, which achieved much recognition for both Taiwan and Indigenous Taiwanese culture worldwide, especially in Asia.

The Truku once inhabited the mountainous regions of Northern Hualien, including the eponymous Taroko gorge. Frequent raids against the neighboring Sakizaya, Kavalan, and Nataroan Amis had made them a feared presence, with the Qing and later Japanese authorities making the containment of the Truku a priority to maintain peace in the Northern Hualien plain. Tensions came to a head when in 1914, the Japanese launched the Truku war, deploying nearly 20,000 soldiers and policemen to finally pacify the Truku. After defeat, many Truku villages were disarmed and relocated to plains. Once classified as another subgroup of the Seediq, the Truku, due to their broad geographical distribution across much of Northern Hualien on the Eastern Coast of Taiwan, had developed unique cultural characteristics over the years. On this basis they successfully campaigned for official recognition in 2004, which also led to the official recognition of the Seediq as a distinct group in 2008.

The Saisiyat reside in Miaoli and Hsinchu in close proximity to the Atayal, leading to a substantial amount of cultural exchange over the years. They are known for holding the Pas’ Ta’ai ceremony which commemorates an ancient conflict with Melanesian Pygmy people that once inhabited Taiwan. Linguistically distinct from the Atayalic peoples, they nevertheless share many features of Atayal culture, such as facial tattoos. However, Saisiyat are thought to have ethnolinguistic ties with the plains indigenous peoples, such as the Pazeh & Taukat/Taokas. This relation on top of oral history suggests that the traditional range of the Saisiyat might have once extended westwardly into the plains and also into the highland regions now considered Atayal territory, and may also suggest that Atayal ethnolinguistic identity might have subsumed other indigenous cultures that might have once inhabited territory now considered Atayal.

Central Mountains

In the central and lower part of the Central mountains in Taiwan reside the Tsou/Cou, Thao, and Bunun. The Tsou inhabit a region across Nantou, Chiayi, and Kaohsiung, and share ethnolinguistic ties with the Kanakanavu and Saaroa further south. A prominent feature of Tsou culture is the male lodge, or kuba, which served as the main political center of Tsou clans and a gathering place for warriors. A similar male lodge system was once used by the Southern plains indigenous groups such as the Siraya. Today, the Tsou are associated with the region around the Yushan and Alishan region, but once held sway across the western side of the Central mountains in regions such as the Puli basin and the western plains. The Luhtu, a Tsou subgroup which controlled parts of the western plains, saw their influence reduced in a series of conflicts with forces of the Kingdom of Tungning, then led by Zheng Jing, the son of Koxinga. Around the same time, the Kanakanavu and Hla’lua, both groups ethno-linguistically related to the Tsou, migrated uphill to seek the protection of the Tsou. The Tsou’s influence was further reduced after outbreaks of smallpox brought in by Han settlers drastically reduced their numbers. Despite decimation from frontier fighting and disease, the Tsou tribes remained geopolitically active — able to effectively wage war, establish diplomacy with the Qing empire and maintain their sovereignty until Japanese occupation. They served as allies of the Qing during the Lin Shuangwen rebellion but also dealt a major defeat to the empire sometime during Kangxi’s reign. The Tsou were also affected by the 228 incident on Feb 28, 1947, when Tsou leaders Yapasuyong Yulunana and Uyongu Yata’uyungana sent Tsou warriors to assist Chiayi militias fighting KMT occupiers. The failed uprising led to the mass execution of Taiwanese rebels, including indigenous leaders such as Yapasuyong Yulunana and Uyongu Yata’uyungana, many of whom were amongst the best educated of their communities.

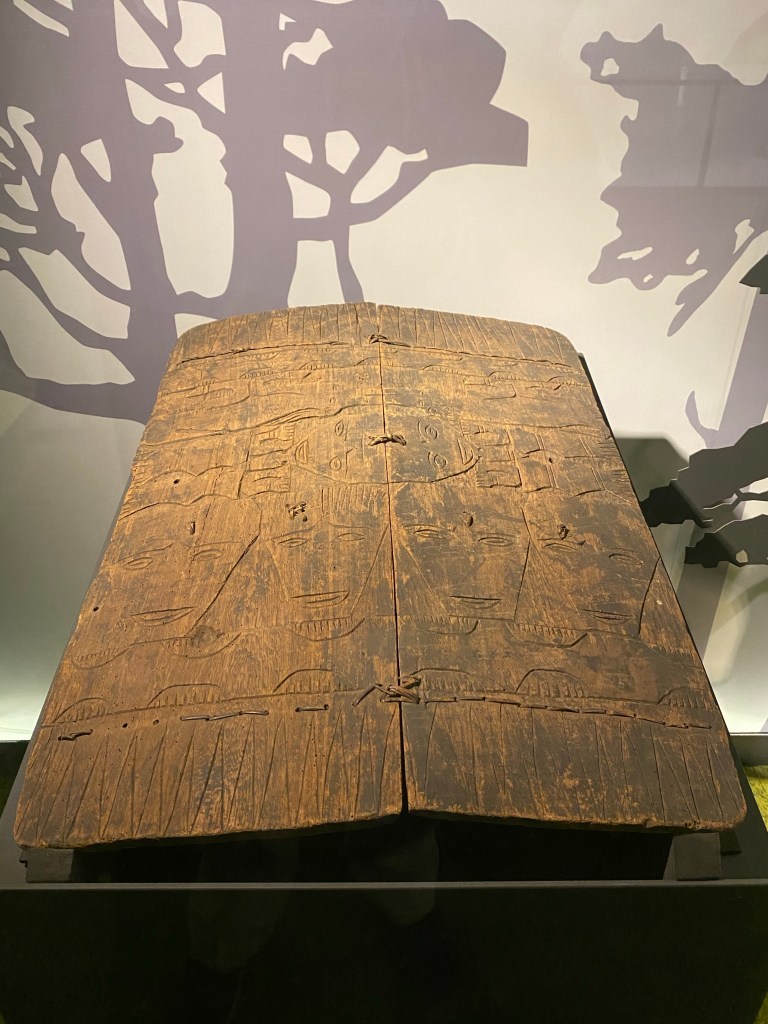

The Bunun are spread across the mountains of Nantou, Kaohsiung, Hualien, and Taitung. Although they likely originated in the region around the Yushan and Alishan mountains, they spread rapidly eastward and southward migration into territory previously occupied by the Tsou, Seediq, Atayal, and Paiwan, possibly due to smallpox outbreaks amongst the Tsou. Due to their close proximity to Yushan, the tallest peak(3952m) in Taiwan, the Bunun often serve as porters, and like their Sherpa counterparts in the Himalayas, possess specialized adaptations for life at high altitudes. A distinctive cultural feature of Bunun is the use of a sophisticated calendar, composed of pictographs carved onto a plank of wood to denote a complex array of traditional ceremonies. These ceremonies not only mark important cultural activities such as the Malahadisa(Ear-shooting festival), a hunting ceremony that serves as a coming of age ritual for boys, but also follow agricultural cycles of important crops, such as the growing and harvesting of millet. Bunun warriors led by Raho Ari and Aliman Sekun were amongst the last in Taiwan to resist Japanese occupation. Japanese ethnologist Mori Ushinosuke, who had befriended Aliman Sekun, managed to study and document Bunun life and culture prior to the incident. Mori noted that unlike other groups like the Atayal and Seediq, the Bunun remained cohesive and provided a united front when facing outsiders like the Japanese. The fighting only died down after the Japanese settled for peace and started recruiting them for the Takasago volunteers corps.

Eastern Coast

On the eastern coast of Taiwan reside the Kavalan, Sakizaya, and Amis. They, along with the Siraya on the western coast and the now extinct Ketagalan-Basay people who inhabited the Taipei basin, are thought to all be speakers of the Eastern Formosan languages.

The Amis are the most populous indigenous group in Taiwan and have traditionally occupied territory across the plains and coasts of Hualien and Taitung. Although they are often considered one group, there are various distinct regional organizations based on tribal and dialectal groupings:

- Nataroan/Nanshi南勢(Orange on map): the Northern division near Hualien city, including settlements such as Cikasuan village

- Siwkolan/Xiugulan秀姑巒(Red on map): occupying much of the Southern half of the Hualien plain

- Tavalong-Vataan/Coastal(Blue on Map): occupying the southern half of Hualien coast, including villages like C’epo

- Farangaw-Maran/Taitung台東(Green on map): occupying most of the Taitung coast, including settlements such as Fa’rangao & Atolan

- Palidaw/Hengchun恆春(Beige on map): communities of Pangcah spread throughout the inner Taitung plain(Luye and Cishang townships) and Hengchun region in Pingtung county

- The Metropolitan Amis: various communities of Amis based in major metropolitan areas around Taiwan

As coastal people, the Amis/Pangcah are well known for their fishing and coastal seafaring traditions. However, not all Amis communities are based around water as settlements such as Kiwit, Ceroh, and Cikasuan are further inland or nestled by mountains. However, a feature uniting the disparate Amis groups is the age based social hierarchy, in which certain societal roles are performed by each age group, with individuals only allowed to progress to the next stage if certain skills are mastered. The leader or chief of an Amis tribe, the Kakitaan, chosen amongst the men of the oldest age group and is responsible for affairs with nearby villages, providing social welfare, and the preservation of traditional knowledge. Amongst the various local chiefs is selected a chief to serve as supreme Chief. As more Chinese settlers arrived in the Eastern plains, the Qing, in an attempt to control the region often cooperated with local Amis leaders, gifting them silk robes, a possible explanation for why ceremonial robes of Amis leaders sometimes resemble Qing era surcoats(補服). One such leader of the Farangaw-Maran, Kolas Mahengheng, served as an important mediator between the Japanese and various Amis and other indigenous groups, preventing or lowering tensions after conflicts and uprisings.

While much of Northern Hualien is today inhabited by the Nataroan Amis, this was not always the case. Before the 1800s, much of what is now Hualien city was the domain of the Sakizaya, a group closely related to the Nataroan Amis. As early as 1632, Spanish records of the Hualien region had recorded the names of various Sakizaya villages, many of which still exist. These villages, spread across Hualien plains to the coast, formed a cohesive political unit that centered around the village of Takobowan Sakor at the foot of Mt Sapodang. Around the 1840’s the Sakizaya formed an agreement to allow the Kavalan who had migrated from Yilan to settle the Karewan area north of the Meilun river and cooperate in defense against Truku raiders. However in 1874, the Qing dynasty began to implement a policy of “opening the mountains and pacifying the savages”(開山撫番), stationing soldiers along the east coast of Taiwan. Initially, the Kavalan and Sakizaya cooperated with Qing forces to keep Truku raiders at bay, but in 1878, harassment by Qing soldiers sparked the Karewan incident, in which Kavalan fighters ambushed local Qing forces and drew in their Sakizaya allies. Despite initial success, the fighting led to a crushing defeat at the hands of the Qing dynasty, ending in the encirclement of Takobowan Sakor. A strategically planted hedge of spiny bamboo had managed to prevent the Qing forces from breaking through however the then chief, Kumud Pazik and his wife Icep Kanasaw had ordered the remaining villagers to flee while they negotiated with the Qing, only to be tortured and executed publicly as the rest of the village was burned. The surviving Sakizaya and Kavalan managed to hide amongst the neighboring Nataroan Amis villages, and suppressed their cultures and languages to avoid detection. More than a century later, the Sakizaya and Kavalan remained reluctant to reveal their identities, with many of their own children growing up identifying as Amis. However, starting from the 90s, Sakizaya and Kavalan members began reclaiming their own identity and culture. In 2002, the Kavalan obtained official recognition by the government, followed by the Sakizaya in 2007. Since 2006, the Kavalan and Sakizaya have jointly held the Palamal or Fire God ceremony to commemorate those who died in the Karewan incident.

The related but now extinct Ketagalan-Basay peoples once lived in the region around modern day Taipei. According to Spanish Chroniclers from the 1600’s, the Basay/Ketagalan were well known for their multilingual capabilities, affinity for trade and maritime activities, and offered their services as craftsmen and smiths to other peoples of the Western Coast. The Kavalan and Amis likely served a similar role on the east coast as attested to in Sakizaya oral history.

Southern Taiwan

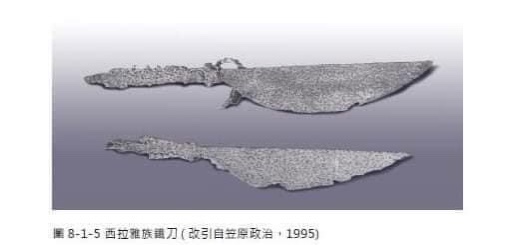

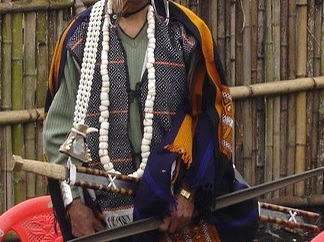

In the southernmost reaches of Taiwan, the land narrows into a peninsula split down the middle by a mountain range. The three predominant ethnolinguistic groups of this region have settled in three distinct zones and while they share many similarities they also have many differences. Highest in the mountains are the Rukai (sometimes written as Drekay). There are 3 theories for the origin of the name. Rukai could be from Ngudradrekai meaning “people who live on the high and cold mountains”, or from a Paiwanic word meaning “upstream, deep mountains, etc.”, referring to the place where the Rukai people live, and the third theory is that it comes from the Puyuma word Rukai, referring to a settlement close to the foot of the mountains. Any of the three implies much about their traditionally preferred territories. Each tribe had its hunting lands and they engaged in slash and burn agriculture. They have a patrilineal society with classes and thus stratified roles. The regalia, decoration of blade scabbards, tattoos and other aesthetic touches set elites apart from commoners. With other tribal groups on all sides, headhunting used to be common – warrior training was communal and there are still festivities to test and celebrate the skills and martial spirit of young men. Eastern Rukai seemed to have influenced the material culture of neighboring tribes on the eastern coast while Western Rukai seemed to have deeply influenced the northern Paiwan to their south, in particular the Kucapungane tribe influencing the Pawanic Paridraya.

Speaking of the Paiwan, the Paridraya represent the northern radiation of Paiwanic tribes from deeper in the mountains westwards towards the foothills abutting Taiwan’s western plain. Though their material culture resembles the Rukai, there are still distinct differences in funerary rites, social stratification, and they are of different language groups. One of the castes of the Paiwan are the Pulima, who serve as cultural torchbearers and craftsmen responsible for creating the 3 treasures of Paiwan culture: the Tjakit knife, glass beads, and ornate clay pots, which were often given as high status gifts during special occasions like weddings, either as a dowry or bride price. Like the Rukai the Paiwan had communal warrior training, some groups having kuba or dedicated male lodges. Other than the northern Paiwan, other groups are known to have a unique “block” on their scabbards which serves an ergonomic function when drawing their blades as well as an additional surface for decor. Certain motifs were reserved for nobility, as were tattoos and certain clothing. The Paiwan were historically eager for trade with Makatao, Hakka and Holo for goods such as cloth, steel, salt and guns and even took on some foreign wives and Chinese farming practices. Yet they also remained defensive and aloof in their mountains and hills, and were still a martially capable people in the early days of Japanese occupation – proving their tenacity in their uprising against disarmament.

While the Paiwan have at times been locally powerful entities on the Qing frontier, Paiwan closer to the southern tip of Taiwan formed rudimentary states. Tjuaquvuquvulj and Longkiaw were both able to establish diplomacy and wage war against foreign powers. Longkiaw was a very interesting case of an indigenous semi-feudal state. Of the 18 tribes of Longkiaw, 14 were southern Paiwan and 4 communities were Seqalu led by four Seqalu chiefs. The Seqalu, a name that may have come from the practice of their chiefs to be carried on sedan chairs, were descended from Pinuyumayan invaders who are said to have conquered the southern Paiwan with witchcraft and superior martial abilities. Though by the end of the 1800s this ruling class was largely assimilated, they retained their governing power and distinct identity within the Paiwan population they ruled. The Seqalu not only managed Paiwan communities but also leased the lowlands out to the Palidaw Amis, Makatao (pingpu), Hakka and Holo newcomers. This state was famously involved in the Rover incident in 1867, where shipwrecked Americans were headhunted by the southern Paiwan, and an ensuing battle with US Marines resulted in a indigenous victory. Later in 1871 a similar Mudan incident occurred, where shipwrecked Ryukuans were killed due to misunderstandings, and this served as a casus-belli for an Imperial Japanese invasion. While the Japanese won, they suffered heavier than expected casualties, partially due to native defense, but also due to disease. These foreign incursions spurred the Qing to modernize Taiwan and close the frontier – a policy which in hindsight was too late to prevent Japanese conquest. This policy of “opening the mountains and pacifying the savages”(開山撫番) would later lead to further clashes between the Qing and indigenous people throughout Taiwan

The ancestors of the Seqalu invaded from the northeast, on the eastern side of the mountain range, near today’s Taitung city. There in that river plain, was a thriving culture that today refers to itself as Pinuyumayan. Japanese ethnographers called them collectively the Puyuma, after the paramount tribe, but that was just the dominant group of the time. They were the ones who had won out against the ancestors of Seqalu, incentivizing their departure from their homeland and their southern conquest. As with the Rukai and Paiwan, the Pinuyumayan had communal warrior training for their males. Each young man was expected to undergo training in hunting, ethics, rituals and warriorship at the Takovan (male lodge) under this Palukkuwan system. Every year the new batch of braves would be required to then go Mangayaw (headhunt) in order to prove their skill and gain insights into the enemy. This Palukkuwan male training can be likened to the popular conception of the Spartan Agoge. Although shielded from the worst of colonization by the mountains, the Pinuyumayan of the east did establish diplomacy with the Qing dynasty, assisted the empire in quashing at least one revolt, and managed the local north-South trade route on the southeastern coast of Taiwan. Their elites would handle the distribution of tribute and goods and like the Rukai and Paiwan, noble families held significant authority and had clan motifs and symbols in their clothing and carved onto their blade scabbards.

Western Plains

The Western Plains of Taiwan were once home to various lowland tribes. Although collectively referred to as Pingpu/Pepo(平鋪), or Plains indigenous peoples, these groups are not necessarily closely related to each other and likely share closer ethnolinguistic ties to highland tribes of the interior. The plains indigenous often leased land to the Han settlers to farmers, leading to conflict with both the settlers and the Qing authorities that often resulted in dispossession of indigenous land. Other factors such as more efficient Chinese farming methods, increased intermarriage, and armed conflict led to the eventual assimilation or migration of many of the plains indigenous. In both Chinese and Japanese records, the plains indigenous were referred to as “cooked savages”(熟番) due to their assimilation into Han Chinese community. Despite Sinicization, many communities maintained an indigenous identity throughout the Qing and Japanese era, but during KMT rule, classification of many plains indigenous as Chinese led to the erosion of Indigenous identity. Today, many Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka people are partially descended from plains indigenous peoples. While yet unrecognized by the Taiwanese government, plains indigenous communities throughout Taiwan have maintained or are in the process of reclaiming their indigenous heritage.

The Siraya, Taivoan, and Makatao of the Southern plains of Tainan and Kaohsiung were amongst the first indigenous peoples of Taiwan to have significant contact with the rest of the world. Initially dealing with Chinese pirates, they later came under the rule of the Dutch VOC and later the Chinese. When the VOC settled Tayuan, a sandbank that is now present day Anping, Tainan, they formed alliances with local Sirayan villages such as Sinckan and Soulang, leasing land for building market towns and occasionally employing them to suppress uprisings of Han Chinese laborers or fend off incursions by other indigenous peoples. However, during the Siege of Fort Zeelandia most of the Siraya quickly defected to Koxinga, who in turn gave them special privileges such as tax exemption and further incentivized them to participate in Confucian education. Many Siraya were adept mediators on the frontier due to their relative fluency in both Han and indigenous cultures. Interestingly enough, Dutch missionaries managed to create a Romanized script for the Sirayan language which was successfully taught to the Siraya. Later Japanese scholars discovered a series of texts now called the Sinckan Manuscripts, which revealed that the script continued to be used by the Siraya as late as 1813, long after the departure of the Dutch. Translations of Biblical books such as the Gospel of Matthew, Dutch dictionaries, and the Sinckan manuscripts would later serve as important resources in the reconstruction of the Sirayan language, which had been lost after the gradual Sinicization of the Sirayan people. Today, the Siraya, Taivoan, and Makatao communities still remain in their traditional areas around Tainan and Kaohsiung, but are also present elsewhere in Taiwan, such as a few Makatao communities on the Pingtung coast, and a few settlements in Hualien and Taitung. Although yet unrecognized by the Taiwanese Government, the local governments of Tainan, Kaohsiung, and Pingtung have recognized the indigenous status of the Siraya, Taivoan, and Makatao.

The Central plains of Taiwan stretching from Miaoli to Chiayi were once home to the Taokas/Taokat, Pazeh, Hoanya, Papora, and Babuza. Early Chinese and Dutch records of the region a powerful tribal confederation known to the Dutch as the Kingdom of Middag which stretched from the Dajia river south to northern Changhua. The kingdom of Middag centered around a cluster of Papora villages, but encompassed Taokat, Pazeh, Hoanya, and Babuza villages. The Influence of Middag over the region vacillated, usually encompassing around 20 settlements and peaking at 27. The King, a hereditary matrilineal position, ruled from the village of Middag/Tatuturo/Dadu(大肚). Early interactions with the Dutch were hostile, with a series of conflicts eventually resulting in a peace signed with the then ruler, a Camachat Aslamie as recorded in VOC records. During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia, forces under Koxinga were sent to negotiate for supplies with the Papora village of Salack(modern day Shalu/沙鹿 ,Taichung). At night, the villagers likely with assistance of other Middag forces, massacred about 1400 of Koxinga’s men, including the commander Chen Ze(陳澤). Later, Koxinga would retaliate by killing nearly every fighting age male of the village as a warning to the rest of Middag. Later during Qing rule, the peoples of Middag fought against the corvee labor tax and further incursions on their lands and sovereignty, which would lead to a series of conflicts between Middag and the Qing government. Eventually, the Qing employed the tactic of “using barbarians to control barbarians”(以番制番) and exploiting internal rifts to great effect, shattering the confederation. Many of the villages decided to leave the plains, negotiating with the Tsou to settle the Puli basin, where their descendants remain today. In 2001, the last native and fluent speaker of the Pazeh language, Pan Jinyu(潘金玉) started teaching the language to classes of Pazeh and scholars. By the time of her death in 2010, at least 10 of her students had become fluent in the language and continue to teach in efforts to revive the language.

In 2016, alongside the formal apology to the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, President Tsai Ing-wen also set into motion a series of legal amendments aimed towards the future recognition of Plains indigenous peoples by the Taiwanese government. In 2022, the Constitutional court ruled in favor of recognition of the indigenous status of the Siraya and other Plains indigenous groups, paving the way for formal recognition in the near future.

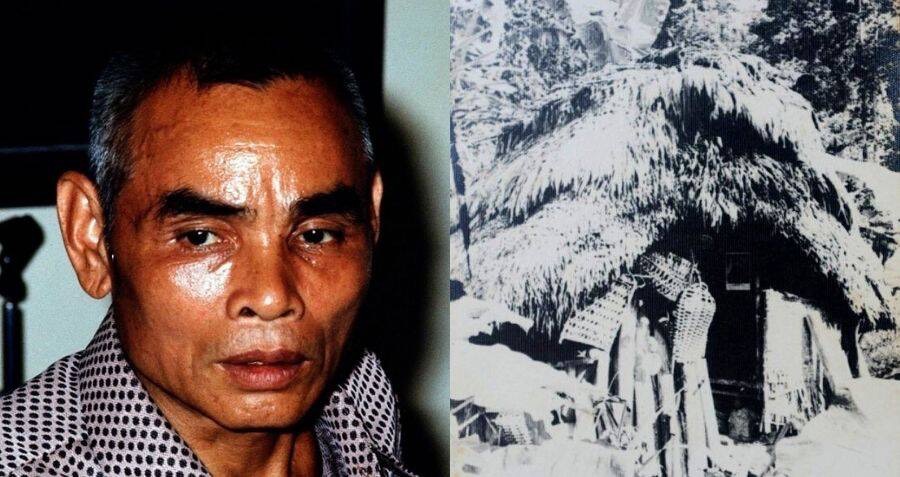

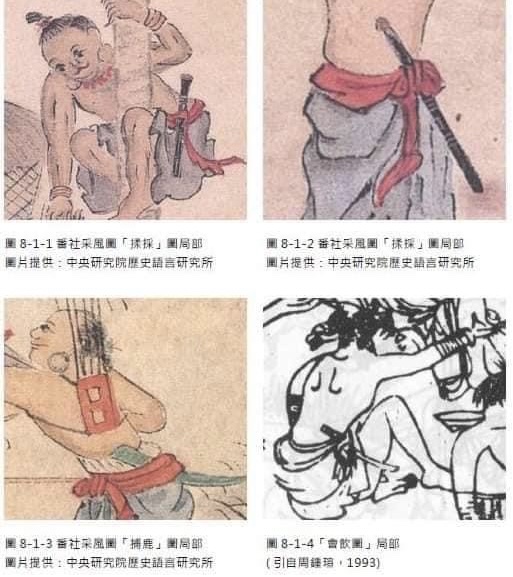

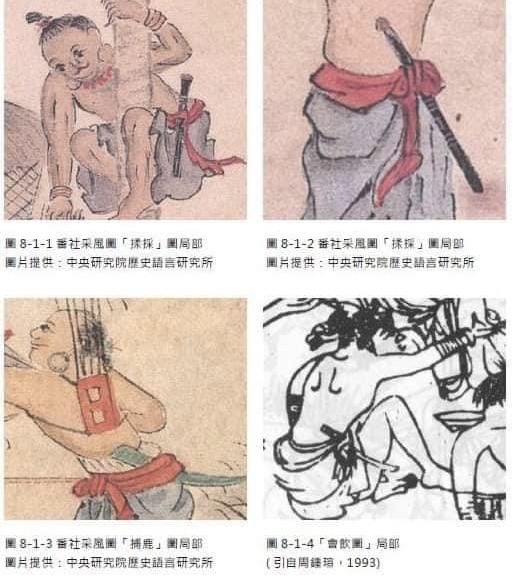

Warrior Cultures

The Indigenous peoples of Taiwan were well regarded for their warrior ability. Throughout history, being shipwrecked on Taiwan carried a high risk of death, as seen in 1616 when a ship full of samurai sent by Murayama Toan found themselves surrounded and annihilated by Indigenous warriors. Some level of endemic tribal warfare was practiced by all groups of Indigenous Taiwanese. The skills that served them well in warfare often overlapped with traditional hunting and survival skills. The practice of headhunting was commonplace and served an important role in society and religion. Occasionally, warfare on a larger scale was conducted between larger political entities either for the control of trade, competition for resources, or conquest. Weapons used by the tribes included spears, bows, and knives. Some groups like the Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, and Amis also used shields. However, knives and swords held a particular significance over other weapons in Indigenous society. Later, firearms, which were introduced by the Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese, became an integral part of indigenous culture. Today, Indigenous Taiwanese are the only Taiwanese civilians allowed to own firearms and hunt in order to carry on their traditions.By the end of the 20th century, the Indigenous Taiwanese had clashed with the Dutch VOC, Ming and Qing Dynasty China, US navy, Imperial Japanese army, and KMT Nationalists. Indigenous Taiwanese warriors also served with distinction in the Imperial Japanese army during WWII, in units of “Takasago volunteers”(Takasago Giyiutai), and were considered expert jungle operatives by both Japanese and allied forces. They were often deployed to secure landing grounds for the Japanese military across the Pacific and operate with minimal logistical support. One such volunteer, Amis soldier Teruo Nakamura(Attun Palalin), was the last known Japanese holdout, having survived in the jungles of Morotai with little else other than his rifle, pot, mirror, and knife.

Today, Indigenous Taiwanese continue to serve in the Taiwanese military and are overwhelmingly represented in athletics both domestically and internationally. Today, Indigenous Taiwanese throughout the island teach their traditional survival skills to tourists, students, and indigenous youth alike and are increasingly becoming a part of mainstream Taiwanese culture and martial ethos.Today, Indigenous Taiwanese no longer headhunt and conduct raids, but still maintain a healthy culture of hunting outdoorsmanship, and athleticism. Thus, are overwhelmingly represented in the Taiwanese military and in athletics both domestically and internationally. These attributes and traditions, such as the wealth of traditional survival skills, are taught to tourists, students, and indigenous youth alike and are increasingly becoming a part of mainstream Taiwanese culture and martial ethos.

Archaeology of Prehistoric Taiwan

Humans have inhabited Taiwan for at least 20,000 years, with traces of habitation have been found on various archaeological sites across the island. The earliest inhabitants of Taiwan possibly arrived during the ice age from the continent via a land bridge or by sea from the Philippines. A site dating to around 5000-6000 BP discovered in Xiaoma cave in Chenggong, Taitung, have revealed the remains of a woman of small stature closely resembling Negrito populations found in the Philippines and Southeast Asia such as the Aetas. Remnants of these pre-pottery peoples have been discovered in sites along the coasts of Taitung and Pingtung, such as the Basian, Siaoma, Longdong and Longkeng caves, where bone awls, fish hooks, and knapped stone tools used for foraging and fishing have been dated to about 15,000-5000BP. A different Paleolithic culture, the Wangxing Culture, has also been discovered in Northwestern Taiwan, and possibly represents a more hunting oriented inland culture. The assemblages found in these sites show a primarily cave dwelling hunter gatherer people with little or no evidence of agriculture. These Paleolithic peoples subsisted off hunting, fishing, and foraging of local plants, only to disappear around 6000-5000 years ago with the arrival of the proto-Austronesians. Around 6000 BP, the Proto-Austronesian Dapengkeng culture, thought to be the progenitor of the Indigenous Taiwanese peoples and the Austronesian speaking peoples, appeared in Taiwan. They brought with them millet and rice agriculture, pottery, bark cloth beaters, and polished stone tools, much more advanced technologies compared to that of the previous inhabitants. Despite coexisting on the island, there seems to be little evidence for the Changbin culture being related to the Dapengkeng culture, with only limited exchange between the two. Instead, the antecedents of the Dapengkeng seem to have arrived from Southern China, from what is today Fujian and with their arrival came the slow retreat of the Changbin culture, with the last remnants holding out on the southeast of Taiwan. A cultural memory of the contact and conflict between the Dapengkeng culture and Changbin culture might remain in folklore that describe a race of “dark-skinned dwarves” that once resided in Taiwan, in particular the Pas’taay festival of Saisiyat.

The stone age predecessor to the knife in Taiwan were polished stone clubs. These clubs likely occupied a similar role in culture and domestic life as knives did when they were introduced. Because of its outward resemblance to the Maori weapon, these clubs are called Patu by archaeologists. These oblong clubs had highly polished flattened surfaces made mostly out of sandstone. These clubs are found throughout the island, and likely spread throughout Austronesia by the Lapita culture. Aside from archaeological finds, these stone clubs have also been venerated in temples throughout Taiwan as ancient relics.

Taiwanese Voyagers

Despite their important role in the dispersal of Austronesian language and culture, Indigenous seafarers of Taiwan leave few traces in both the archaeological and historical record. However, they are not entirely absent. Song era scholar Zhao Rugua(趙汝适, 1170–1231AD) recalls raids on the Fujianese coast by the “Pi-sho-ye barbarians” from Taiwan.

“The language of Pi-sho-ye cannot be understood, and traders do not resort to the country. The people go naked and are in a state of primitive savagery like beasts.

The savages come to make raids and, as their coming cannot be foreseen, many of our people have fallen victims to their cannibalism, a great grief to the people… During the period shun-hi (1174-1190 AD) their chiefs were in the habit of assembling parties of several hundreds to make sudden attacks on the villages …in Quanzhou-fu…

They were fond of iron vessels.… one could get rid of them by closing the entrance door, from which they would only wrench the iron knocker and go away… When attacking an enemy, they are armed with javelins to which are attached ropes of over a hundred feet in length, in order to recover them after throwing; for they put such value on the iron of which these weapons are made, that they cannot bear to lose them.

They do not sail in junks or boats, but lash bamboo into rafts, which can be folded up like screens, so, when hard pressed, a number of them can lift them up and escape by swimming off with them”

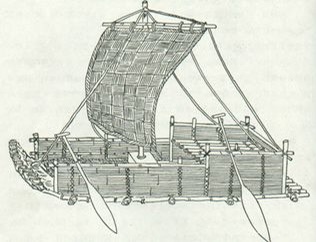

The Name “Pi-sho-ye” once again pops up in the writings of the Yuan era scholar Ma Duanlin(馬端臨), who describes them as originating from the Southwestern coast of Taiwan. Potential sources of the name “Pi-sho-ye” might be the Pazeh of the Central Western coast or the Basay in Northern Coastal Taiwan. The preferred method of transport of the Pi-Sho-ye, bamboo raft is also well documented in Taiwan, as over 700 years later, maritime researcher GRG Worcester witnessed these craft still being used on both sides of the Taiwanese coast. Today, rafts continue to be used by Taiwanese fishermen of both Han Chinese and Indigenous descent, with bamboo now replaced with PVC pipes.

In the 1600’s, Spanish Chroniclers noted that the Basay/Ketagalan were well known for their multilingual capabilities, affinity for trade and maritime activities, and served as itinerant craftsmen and smiths to other peoples along the Western Coast. On the east coast, a 1802 Japanese drawing records the details of an Amis raft from Ceroh(港口), complete with sail, rigging, steering oars, and bulwarks stitched to a bamboo frame on which another platform was secured. This relatively complex raft was likely intended for more than just fishing, but rather for transport and trade. A recent collaboration between the Fa’rangaw Amis and experts from the Solomon Islands led by Dr. Simon Salopuka managed to use their own oral history to successfully recreate a seaworthy raft entirely out of techniques and materials of the indigenous Taiwanese. Most notably, the sail was made from woven leaves, a tradition shared by the Amis, Solomon Islanders, and various other Austronesian peoples. As the Out of Taiwan hypothesis for the dispersal of Austronesian languages has gradually become scientific consensus, many scholars believe, from genetic evidence, that individuals related to the Amis, Rukai, and Paiwan departed from eastern Taitung near the modern day Fa’rangaw settlement were the first Austronesians to make the perilous journey our of Taiwan, eventually settling most of Island SouthEast Asia, Southern Vietnam, Micronesia, Polynesia, and beyond.

Early Trade Networks

Evidence of well established trade routes between Taiwan, Luzon, and Southern Vietnam date to at least 2000 BC. Referred to as the Maritime Jade Road, the trade of nephritic jade amulets, pendants, and earrings, referred to as Lingling-O, was highly prized throughout Neolithic SouthEast Asia. Fengtian Jade, mined from the Fengtian site in Hualien, Taiwan, is particularly common in Neolithic sites in the Philippines and Southern Vietnam. The presence of tools used to mine and process jade blanks and finished ornaments seems to indicate that there was an industry around jade in the Eastern Coast of Taiwan. Jade was a chief export to other regions of Taiwan and the Philippines, where it was traded to the rest of Southeast Asia. The uniformity of certain types of jade products throughout the region has led many experts to postulate the existence of a mechanism for which skills were transferred, possibly in the form of itinerant craftsmen or resettlement of skilled workers. This trade network might have laid the groundwork for the transference of other technologies further down the road, such as glass, bronze, and iron working.

References in later Chinese, European, and Japanese sources to indigenous craft from the Philippines and Malaysia reaching Taiwan suggests that while the trade died down in later years, contact was not entirely lost. This is not to mention the arrival of Orchid Island/Botel Tobago by Batanes islanders from the Philippines, who settled the original inhabitants to eventually become the Yami/Tao people that inhabit the island today. The Batanes islanders and the Yami/Tao of Orchid island remained in contact until around 300 BP.

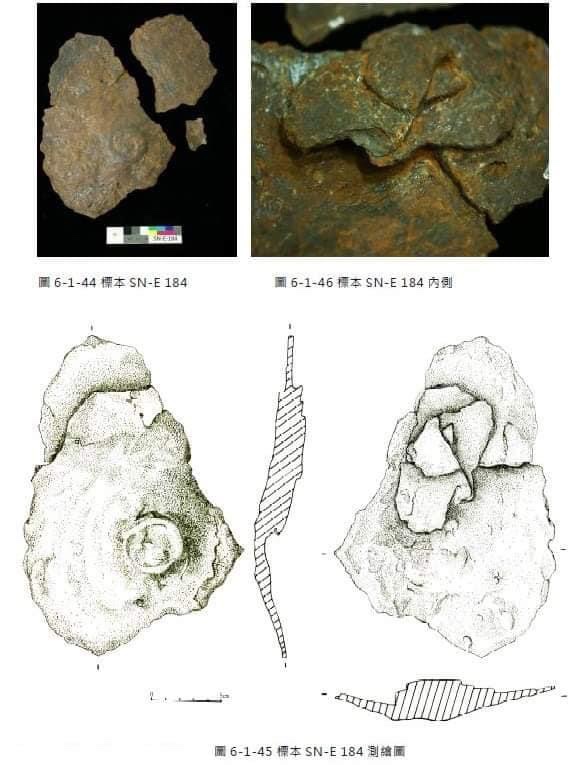

Archaeological Evidence of Metallurgy in Taiwan

The earliest signs of Metallurgy were found in South Eastern Taiwan at the Jiuxianglan, Beinan, and Guishan sites(sites that bear some resemblance to the later Paiwan and Puyuma cultures), where evidence for Glass, Copper, and iron working have been discovered, dating to as early as 500 BC. This roughly coincides with the Iron age of the Philippines, where iron producing technology had been introduced by the Sa Huynh culture of Vietnam, associated with the Austronesian Cham people. Trade between the cultures is further reflected by andthe sudden appearance of copper in Taiwan, which is otherwise extremely rare. The presence of casting molds carved from indigenous Taiwanese sandstone indicates a nativization of bronze working skills, however the scarcity of copper in Taiwan suggests that much of the metal had to be imported or recycled. Bronze and Iron working technology likely traveled along the long established trade network between South Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan, which had earlier facilitated the spread of lingling-o style ornaments.

The Iron age Jingpu culture in what is now Coastal Hualien and Taitung is possibly influenced by the early metallurgy seen in Southeastern Taiwan. Analysis of the slag and remnants of smelting equipment suggests that they likely employed a double piston bloomery similar to those still used in Island and Mainland Southeast Asia. The ironworking of the Jingpu culture, associated with the Amis people, might be representative of the metallurgy of much of the east coast of Taiwan.

In northern Taiwan, 2 main sites, the Shisanhang site near the mouth of the Tamsui river and the Hanben/Blihun site in Yilan near the mouth of the Heping river represent another possibly distinct iron working tradition, where bronze casting, single and double edged knives/daggers, and furnaces were discovered. They represent some of the first sites in Taiwan to show large-scale smelting of iron, as demonstrated by the large amounts of slag present. Analysis of slag and the remains of possible bloomeries indicate that iron sand was used to produce iron/low carbon steel. The evidence for ironworking predates Chinese trade goods discovered at the Shihsanhang site, which might suggest either spread of ironworking from a source aside from China or indigenous development of ironworking. Genetic testing on remains from the Hanben/Blihun site show a genetic relationship with the Atayal and other indigenous peoples of Northern Taiwan, which suggests that ironworking was present early on amongst the indigenous groups of Northern Taiwan.

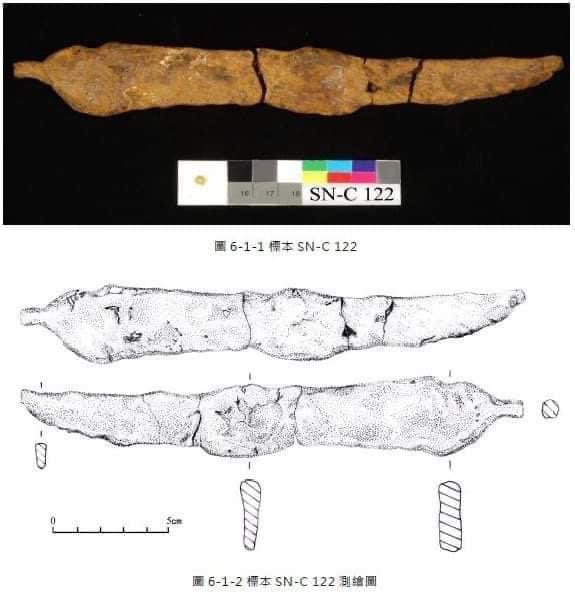

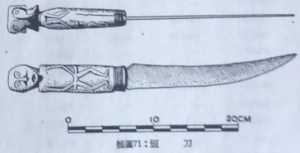

Interestingly enough, the Paiwan treasure ancient iron daggers with bronze handles referred to as “tikuzan ni tagarus” that greatly resemble those found in early Iron Age sites throughout Taiwan. The daggers are often rusted and patinated and served as family heirlooms of aristocratic families. The apparent age and importance of these artifacts might suggest that these daggers are possibly the relics from an older time, as breakdown of trade between Taiwan and the rest of Southeast Asia resulted in loss of access to copper and thus the ability to produce such items.

Archaeological sites Throughout Taiwan have yielded a variety of blade forms. A site at Shenei(社內), Tainan, dating to the 17th century, have yielded several single edged blades of a similar profile. However due to the semi-tropical climate of Taiwan, many of these finds are in poor condition, and scabbard and other fittings have not survived. Yet the profile of these knives vaguely resemble contemporary iconographic depictions of Sirayan knives during the early Qing dynasty and surviving examples such as a knife in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer collection obtained in 1743. The profile of the knives, which resemble an intermediate form between Southern Taiwanese knives and the straight-backed variety of Lalaw, might represent a style of knife preferred by the now largely assimilated plains indigenous/Pingpu people.

Metallurgical practices in Taiwan

Throughout the modern and early modern period, Indigenous blades have had influences from Chinese and Japanese metallurgical practices, but there is evidence to suggest that indigenous smiths can trace their practice from earlier in history. After all, the variation of blade design across Taiwan makes it unlikely that these blades were supplied purely from trade. As stated earlier, iron smithing seems to have been introduced to Taiwan about 2000 BP from the Philippines, many centuries before any major Chinese settlement occurred. The ubiquity of knives amongst pre-colonial indigenous culture and the absence of lithic technology indicates that indigenous metallurgy was once widespread across Taiwan.

Despite evidence of indigenous foundries, iron itself seems to have remained quite scarce in Taiwan, as demonstrated by its value to the aforementioned “Pi-sho-ye” raiders. The looting of mundane metal objects such as iron door knockers suggests that while the Pi-sho-ye were metal poor, they fully expected smiths back home to be capable of converting the iron into more useful implements. Indigenous foundries were only capable of producing Iron/low-carbon steel, but increased trade of Chinese goods such as woks provided a source of high carbon steel. The 2 distinct sources for high and low carbon steel might have influenced the composition of historical indigenous blades. Most analysis of the composition of Indigenous knives show a spine/body made largely of low carbon steel with a high carbon edge. This was achieved with either the use of a hard edge insert or rough Sanmai construction, both techniques which are still practiced by indigenous and Chinese smiths in Taiwan. Heat treatment largely takes the form of edge quenching, keeping the spine of the blade softer and thus more resilient.

Outsourcing knife production to other groups likely occurred early on, as some cultures, like the Basay/Ketagalan served as itinerant smiths for other communities. It is possible Chinese settlers provided services as smiths to indigenous communities, and an exchange of materials, styles, and techniques occurred. Chinese and Sinicized Pingpu/Plains indigenous smiths were likely commissioned by indigenous peoples to make certain designs, eventually taking over most of the market for indigenous knife making and outcompeting local smiths. This is especially likely for some groups like the Seqalu in Southern Taiwan, who held suzerainty over Pingpu and Han villages. A few examples of long Tjakit knives associated with the region not only greatly resemble each other in detail, but also exhibit decorative features that are more common amongst Chinese and Vietnamese craftsmen. The potential Vietnamese influence might be the result of 2 historical incidents, with the influx of Chinese mercenaries fleeing the failed Tayson rebellion and the arrival of the Black Flag army to support the short-lived Republic of Formosa. Knives, alongside rifles and salt were also one of the main items Chinese traders often brought to the villages for exchange. However, outsourcing remained only one source of blades as Japanese scholars and officials recorded various instances of Chinese smiths being hired to help set up forges in indigenous villages throughout Taiwan.

With the arrival of the Japanese, newer techniques and styles were introduced, and some indigenous smiths were even press-ganged by the Japanese for the war effort. One such example is the Truku village of Tongmen in Hualien, where according to the locals, the colonial Japanese government resettled families of blade smiths, where they were taught Japanese techniques and transformed into a sort of cottage industry to supply blades for the Japanese throughout the 19th and 20th century.

Between the end of WWII and the ROC leaving the UN, many mass produced souvenir knives were sold to American personnel stationed in Taiwan. These often contained a mix of motifs and features from cultures across Taiwan, and were likely made specifically for the Tourism industry. Many of these knives have since surfaced on eBay and other auction sites.

Today, there are only a handful of traditional knife makers around, with many knives made by Han Chinese catering to an indigenous clientele. Blades are often commissioned by tribesmen, who then make the necessary alterations and fittings themselves. There is evidence to suggest that such a relationship existed in the past, as many antique blades possess Chinese maker’s marks, along with elements of Chinese decoration like Chinese coins, and Chinese styled artistry and inlaying. Today, most Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma craftsmen purchase knife blanks forged to their specifications by ethnic Chinese smiths in the area, and make their own fittings for the knives. In the 2000s, smiths in Daxi, Taoyuan, have started forging knives to indigenous designs as a result of participating in academic efforts to replicate lalaw from museum and archaeological specimens. They have since continued to make these knives and expanded to include designs from other parts of Taiwan, which are in high demand among indigenous and non indigenous knife enthusiasts.

Indigenous smiths are still around, but are harder to find. A Truku village in Tongmen(同門, Bronze gate in Chinese, the name is arbitrary), has long been known as a hotspot for indigenous knife making. During colonial Japanese rule, they were resettled by the Japanese in the region and press-ganged to produce blades for the war effort. There are currently around 6 active blade smithing families in the village, with the oldest family going back 6 generations. Today, these smiths no longer make knives of Japanese designs, but instead, create traditionally patterned knives alongside a variety of kitchen and farm bladed tools and modern knives. These smiths have also retained traditional techniques, such as burning the tang into pre carved wooden handles and edge quenching their blades in water so as to maintain a hard edge, but a softer, more resilient spine. While most Tongmen blades are mono steel made from truck leaf springs and other modern metals, the Tongmen smiths still retain the practice of adding a hard edge insert in some blades.

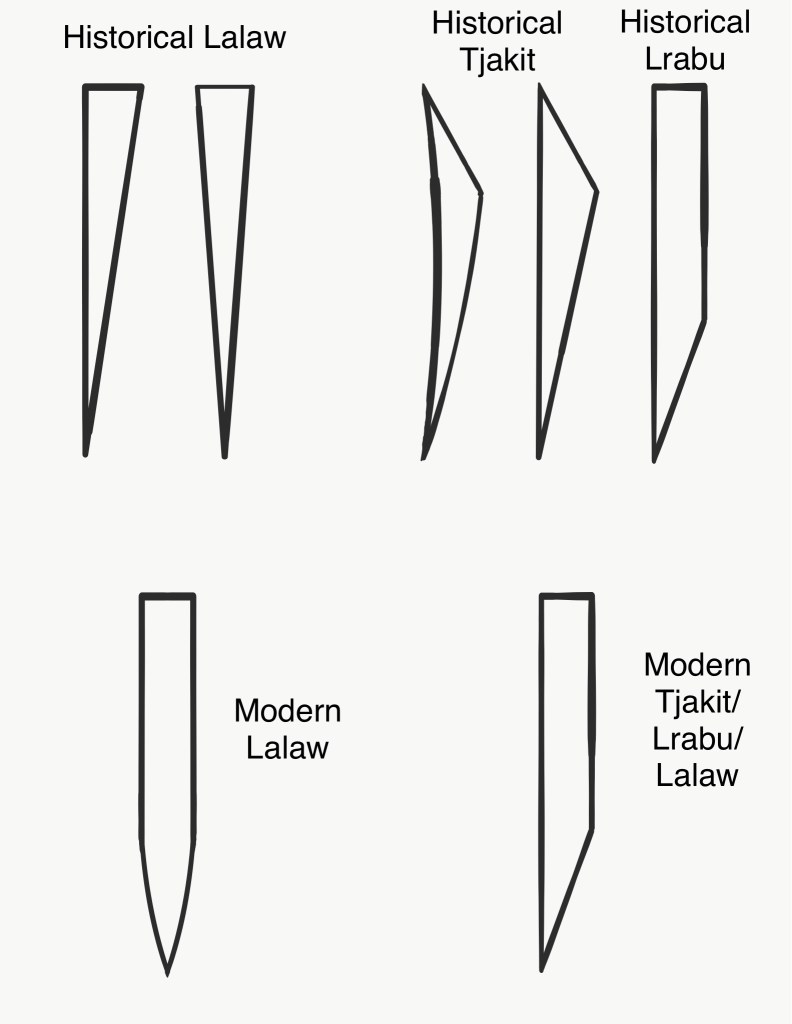

The modernization of metallurgical practices has caused a gradual change in the knives themselves. Historic lalaw were often flat ground, either with or without a chisel grind, likely as a result of bevels being forged out rather than ground. Today, lalaw and many other indigenous knives feature a convex grind, with belt sanders becoming a common presence of throughout Taiwan. Paiwan Tjakit historically had a triangular chisel ground cross section with an edge bevel near the spine. The flat inner section sometimes had a hollow grind similar to the Japanese Urasuki. With Japanese influence and gradual change, the design of southern knives have slowly converged to resemble the Rukai Lrabu in both the design of fittings and cross section, which was essentially a chisel ground knife with an edge bevel closer to the edge.

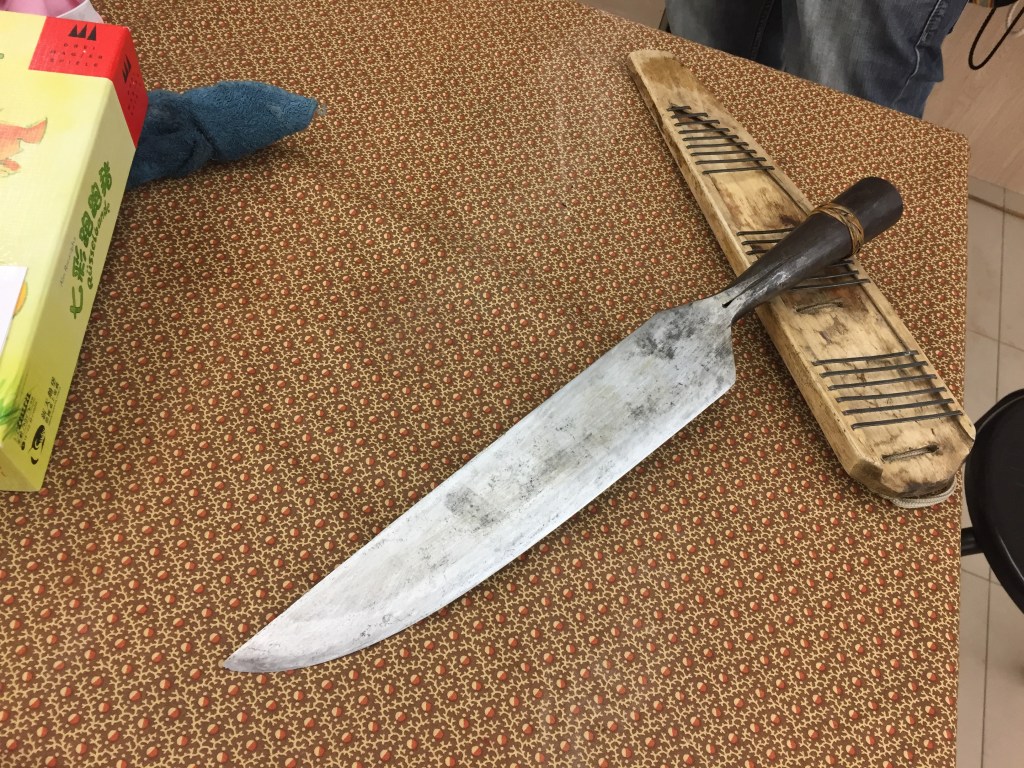

The Formosan Knife

By the time the Indigenous Taiwanese entered history, each tribe had their signature style of knife. However, all knife styles shared a set of commonalities. Most blades are un-fullered and all were chisel ground to facilitate their use as machetes. In all cultures, there are 2 handle variations: either a socketed handle construction, which allows them to be hafted, or a tapered tang which is hammered/burned into a piece of wood serving as the handle. All tribes in Taiwan had some form of wooden scabbard with an open face on one side. This usually consists of a recess carved into the general profile of the knife on one side, with the knife held by either with wood, rattan wraps, or series of metal wires and plates nailed in place to keep it secure. This was supposedly done to prevent moisture build up that would occur inside an enclosed scabbard. Scabbards of southeastern Taiwan are generally more ornate and carved with culturally significant motifs and patterns.

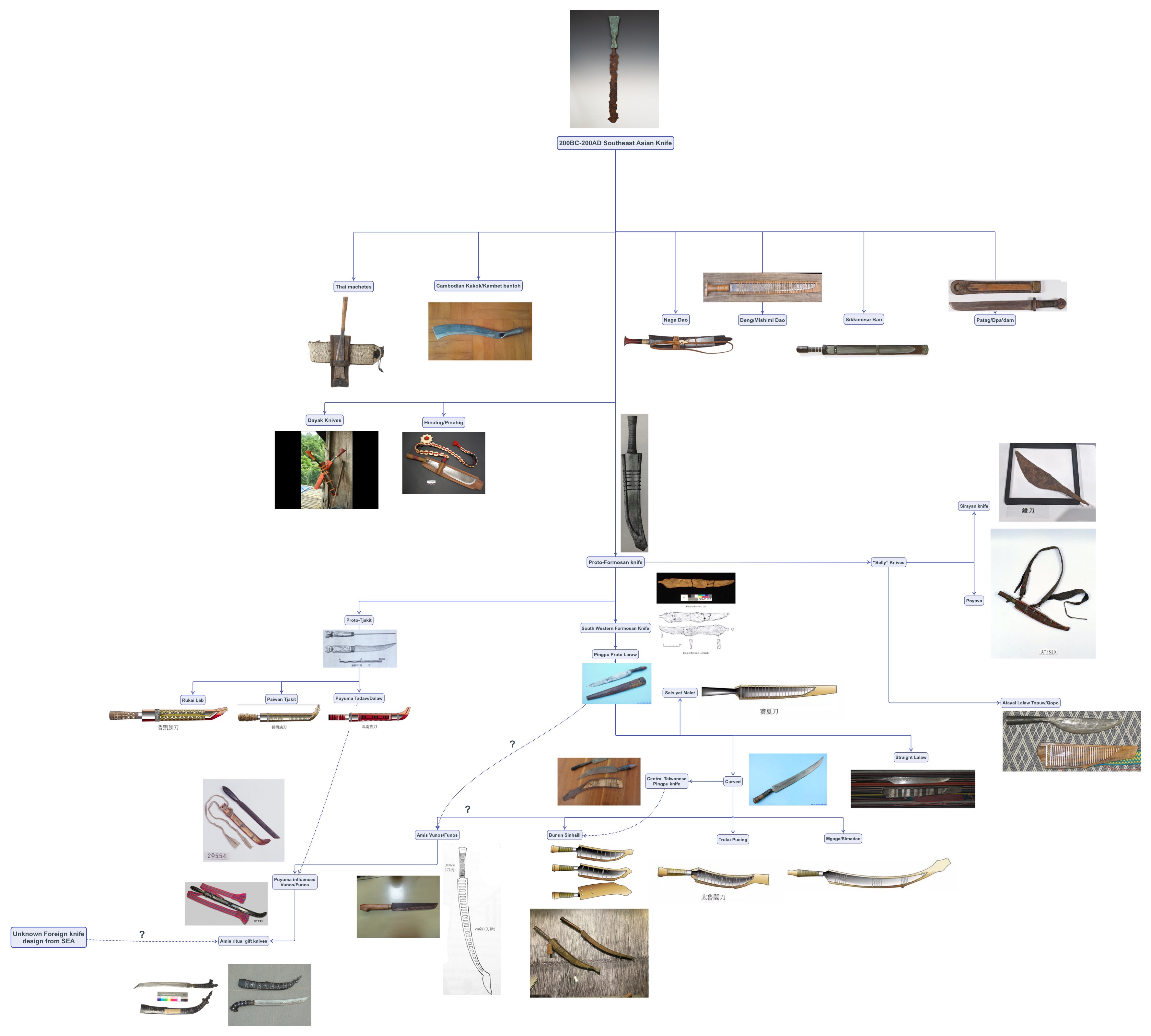

While no typology exists for the knives of Taiwan, traditional knives can be roughly divided into 2 or 3 groups based on probable spread, geography, and blade profile and other characteristics: The Northwestern Atayalic style lalaw featuring a wide tapering blade. The Tsouic “Poyava” type knives which feature a single edge barons-like profile, and the Southern Paiwanic Tjakit type narrow bladed knives. While examples of knives and swords of the Lowland tribes still exist, they are not numerous enough to determine tribal and geographic affiliation, especially since most have been removed from their historical and cultural context. However, the wide variety of knives attributed to lowland cultures makes it probable that many of the established knife designs found throughout Taiwan may have originated in the Western Plains.

The First Knives

It is difficult to determine exactly what the first kinds of knife appeared in Taiwan were like. Archaeological sources and overseas collections may help confirm the antiquity of several designs. Archaeological sites across the Southwestern plain, dating to the 17th century, yielded several blades of similar profile, however due to the semi-tropical climate of Taiwan, many of these archaeological findings are in poor condition. For these extent examples, the scabbard and other fittings do not survive, but these knives vaguely resemble contemporary iconographic depictions of Sirayan knives used by Sirayan tribesmen by artists of the early Qing dynasty.

A particular knife kept in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer collection also shows some resemblance to the archaeological examples found in Southwestern Taiwan. The knife was recorded to have been in the collection since 1743 but could possibly be several years/decades older, thus more or less contemporaneous with the Qing depictions of Sirayan knives. Having been spirited away to Europe centuries ago, this knife is possibly the oldest intact Formosan knife, spared from environmental degradation and recycling, but as a result of this particular knife’s age and lack of records before its acquisition, it is difficult, if not impossible to determine exactly when and where this knife was made.

The knife is 44cm in length, and the scabbard showed standard characteristics such as the wires used to secure the knife, and also features a variation of the upturned end that is nearly ubiquitous in all the scabbards used by the Indigenous Taiwanese. The handle is the only one of its kind known, as most handles of Formosan blades narrow towards the blade, whereas this particular example is waisted. The blade profile resembles neither Southern nor Northern styles of blade, but rather has features of both. It has a single bevel cross section, like Northern blades, but the junction between the handle and blade resembles that of Southern Paiwanic blades. The blade profile resembles a fusion of the 2 styles, with a gradual taper which suddenly curves at the last section into a tip, but remains narrow at the base. It is possible that this particular knife represents an early type of knife from which the other styles developed from, but it could also represent a regional style no longer in existence.

Lowland “Pingpu” Knife Designs

It is difficult to classify and appreciate the variety knives used by the various lowland Pingpu knives, given their own disparate origins and long histories. Many, like the knives of the Pazeh and other North-central Tribes of the western plain resemble Atayal, Seediq, and Saisaiyat knives. This might be a result of possible shared heritage between the groups or frequent trade. South Western tribes often had interactions with the Rukai and Paiwan, and possibly shared in their knife design, however, this has been difficult to establish due to the small number of examples positively identified with the Southwestern lowland tribes. This wide variety of designs might reflect either a source from which other designs branched out, or a accumulation of designs from various regions, within and outside of Taiwan.

A common form of knife positively identified with lowland cultures is a short, straight-backed variety similar to some smaller, lalaw style northern knives. The design also happens to resemble fighting knives used by the Han Chinese that emigrated and eventually assimilated the Lowland tribes. The sheaths often displays artistic motifs often resemble Chinese art, possibly indicating that the production of these knives were possibly influenced by Chinese craftsmen.

Another variation of Pingpu lowland knife a semicircular bellied blade attributed to Sirayan peoples, as archaeological examples have been found. While similarity with Tsouic knives might be coincidental, as there’s limited evidence of transmission between cultures, its possible that this form of knife might have represented a type of knife that was once more widespread across Taiwan.

The Tsou Pojava

The Tsou Pojava/Poyave(pronounced Po-Yava), represents a class of knives that are used by peoples living along the Central Mountain range of Taiwan. The profile of the knife resembles an elongated semicircle and distinct from other Formosan knives.

The Tsou, living in the region surrounding Alishan national park, use these knives called poyave no sungcu, meaning straight knife, accompanied by with a Kacace, an ornate belt beaded with cowrie shells and other decorative materials. The sheaths of these knives are often painted red as red was believed to be the favored color of their war god, and a wooden strip was also often attached to the back of the sheath. Unlike many sheaths of other peoples in Taiwan, in addition to wire, Tsou sheaths would also have long, flat places of metal varying in width. In the past, villages had forges which, according to Japanese records, were set up in part, by Han smiths from the lowlands. The suspension system for the knives were different in the north and south, as in the north the Poyave would’ve been tied to the waist by sword belt and shoulder strap whereas in the south, the swordbelt would be the only means of suspension.

The Thao people living nearby the Sun Moon lake also have knives with a similar profile to the Poyave. In Thao society, the Skapamumu clan was in control of all metal work, which were traded for by other clans for other goods. Fittings were similar to the Tsou, where a belt and a shoulder strap were used. The Kanakanavu people further south also used similar knives. The Bunun, who occupy territory that envelopes the Tsou, Thao, and Kanakanavu use a large variety of knife designs, but also use knives similar to the Poyave.

The Atayal also used knives similar to the Pojava called the Lalaw Topuw, which resembles a Barong in it’s semicircular blade profile, except for the fact that the back of the blade is completely straight, and features no false edge. The Atayal lalaw topuw was used more as a tool, were mostly socketed(I have yet to find one that isn’t), and usually under a foot long. When hafted(a common practice), it could be referred to as a Qopo.

As stated in the segment above, archaeological examples of knives attributed to the Siraya also resemble the Pojava and Lalaw Topuw, and were mostly smaller examples under a foot long. The disparate nature of the distribution of these knives could possibly indicate a once larger range and greater popularity throughout Taiwan that has since been reduced to what we can see now.

Northern Knife Designs

The knives of the indigenous peoples of Northern Taiwan encompassing the Atayal, Seediq, Truku, Amis, Bunun, Saisiyat, and various plains tribes share general features and methods of construction. Although the features of the knives are very consistent between the different peoples using them, these cultures are not necessarily directly related to each other, with some being part of same macro group while others coming into contact via migrations.

These Northern knives have a variety of blade profiles, but share a few commonalities. The blades are generally flat or convex ground, sometimes featuring a one sided chisel grind. A universal feature of these knives is the considerable width of the blade at the base and a relatively narrow tang, thus the tang is situated near the center of the blade, so while there is no guard, the blade extends past the fingers essentially forming a choil/heel on either side of the handle. The entire blade is usually canted forward, though the degree varies greatly between knives.

The Atayalic peoples, Atayal, Seediq, and Truku, use knives that display a range of variation depending on geographic, functional, and cultural influences. According to the Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines, Atayal knife profiles are straight in the North and become more curved further south. However, this statement is likely an overgeneralization and challenged by the multiple examples of curved blades in the collection of the Wulai Atayal Museum(at the Northern most tip of Atayal territory), photographic, oral, and archaeological evidence. Oral sources have also suggested that straight backed knives came into popularity after the arrival of Japanese as they were influenced by bayonet designs. these straight knives sometimes featured a canted handle and usually had a consistent distal taper from the base of the blade to the tip, where it often tapers more dramatically. The Saisiyat Malat knife more or less resembles a variation of straight-bladed lalaw, with the Saisiyat possibly having shared the design after coming into contact with the Atayal, or having inherited the design from the indigenous cultures of the northwestern plain distantly related to both the Atayal and Saisiyat.

Curved Atayal knives are indistinguishable from Seediq knives. The knives are usually canted forward and feature a consistent curve and distal taper, thus making the knife a good chopping and cutting tool. The knife curves back so that the point is closer inline with the handle, which makes the knife useful for thrusting as well. These knives were usually 2-3 feet long, but large knives intended for headhunting and warfare can reach gigantic proportions up to 4 feet. Truku knives share most features of Atayal and Seediq knives, but their utility knives tend to remain mostly straight and only curving and tapering at about ½ to ⅔ of the length.

The variety of knives used by the Atayal, Seediq, and Truku have specific names which reflect their function and usage. The general term, Lalaw or Lalaw behuw(Pucing is another term used by some Atayal groups and the Truku), were often used for hunting knives with about 2-3 feet in length. Takis seems to have been another term used for these knives in some Atayal dialects. Smaller lalaw which were used as utility knives, have also been referred to as Muli in Atayal, and sometimes hafted for use as a spear or polearm. The large meter long war swords were sometimes referred to as the Mgaga in Atayal, and Slmadac in Seediq. They held more ceremonial and cultural significance, and were intended for use in ritual warfare and headhunting. They were also less common than the other examples, and more often than not, belonged to the more accomplished and respected individuals of a village.

The Atayal, Truku, and Seediq have many explanations for variations in blade lengths. While one might imagine blade lengths of knives used in deeper, wooded areas might be shorter and thus less prone to be caught in the bush, this is generally not the case. An explanation, while often framed as a joke, states that longer blades were more effective against the sessile Han Chinese peoples, who generally dug in for a fight, while shorter blades were more effective in skirmishing against tribal enemies, as shorter blades and lightning fast reactions could mean life or death. This, while thrown around by tribesmen as a joke, might explain the geographic distribution of blade lengths, as the Truku, despite living near the open plains of Hualien, often in contact with neighboring Seediq, Amis, and Bunun, often used short blades, while the Atayal and Seediq in mountainous and densely forested areas generally used longer blades, possibly due to contact with the Chinese, who sometimes ventured into tribal territories for timber.

Northern Bunun Sinhailee knives resemble Atayalic knives in most respects, with their smaller knives resembling the Truku Pucing and larger knives resembling the Slmadac/Mgaga war swords. Amis peoples in contact with the Truku, Seediq, and Bunun often adopted blades similar to the curved lalaw.

Northern Scabbards and Fittings

In most Northern knives, the scabbard consists of a plank of wood with a recess carved into one side, with wires stapled across the opening to keep the knife in place, but usually, the friction fit alone is enough to keep the knife in place. An explanation often given is that these open sided scabbards prevented the trapping of moisture around the knife. Traditionally, these scabbards are either trapezoidal in shape for straight backed knives, or for curved knives, follow the shape of the blade and feature a “stock”at the end of the handle, often held when unsheathing the knife. This stock is often the main varying feature between different designs. Many have tried to make the case that these variations in scabbard design could be used to differentiate the knives used by different peoples; however, given that we often see the same variations in the scabbards used by each tribe, it is likely not a reliable indicator. These stocks either resemble a rough diamond pattern, with protrusions on both sides or a “gunstock/fishtail”, with a protrusion only on the bottom side. Back in the old days, long tassels of human hair from victims of head hunting would have been used to decorate the stock. The scabbard is carved to fit the entire blade and over hang a bit, with “throat” of the scabbard is carved into the shape of the “finger guard”. This serves as a sort of platform for the thumb to push off as the knife is unsheathed. According to some tribesmen, the wood of scabbard can be used as kindling for fire, and may have been made of easily flammable wood for this purpose.

Two styles of handle construction seem to be prominent among these knives, with neither dominating in any one region. One style is the simple socketed handle, present on knives throughout Taiwan of all lengths and designs. Generally, the top end of the socket is left open. One explanation was to prevent moisture buildup within the socket. Smaller blades of socketed construction were often hafted for use as spears, javelins, and polearms, and were also used in the unique practice of mounting a “bayonet” on longbows when closing the distance with animals or enemies. The wooden handle, while not allowing for such versatile use, is nonetheless widespread. The tang of the knife was shaped into a spike, then burned or rammed into a conical piece of wood, and held by friction. While the tang wasn’t usually long enough to fully pass through the handle, when it did, it wasn’t penned, but often just bent over, much like a Chinese meat cleaver. The wooden handle, to prevent splitting, was reinforced with wire or organic material such as rattan or ramie fibers wrapped/woven around as a grip. Sometimes, a metal ferrule is fitted at the junction between blade and handle, however, this feature is mostly seen on knives made today and rarer in the past. The blade was rarely pinned to the handle or glued, although there is a method attested by some, where the tang was deliberately rusted in the handle for a better friction fit. Both types of handles were slightly oval in cross section to facilitate edge alignment.

These swords are usually just tied around the “true waist”, and could thus be removed whenever necessary. The knot was usually some sort of bowline knot that was easy to unfasten. A woven portion was often incorporated into the belt. This practice is slightly different from Southern Tribes.

Southern Knives

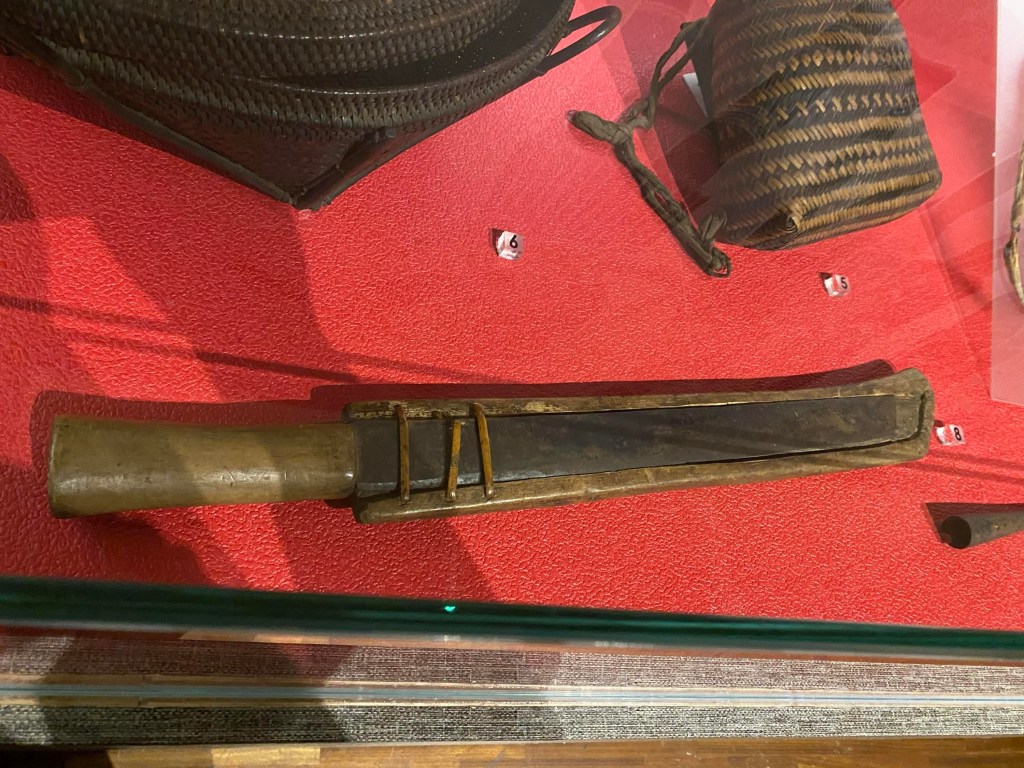

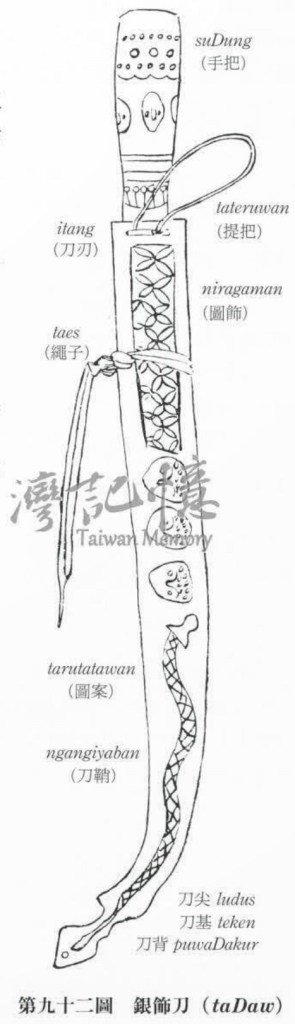

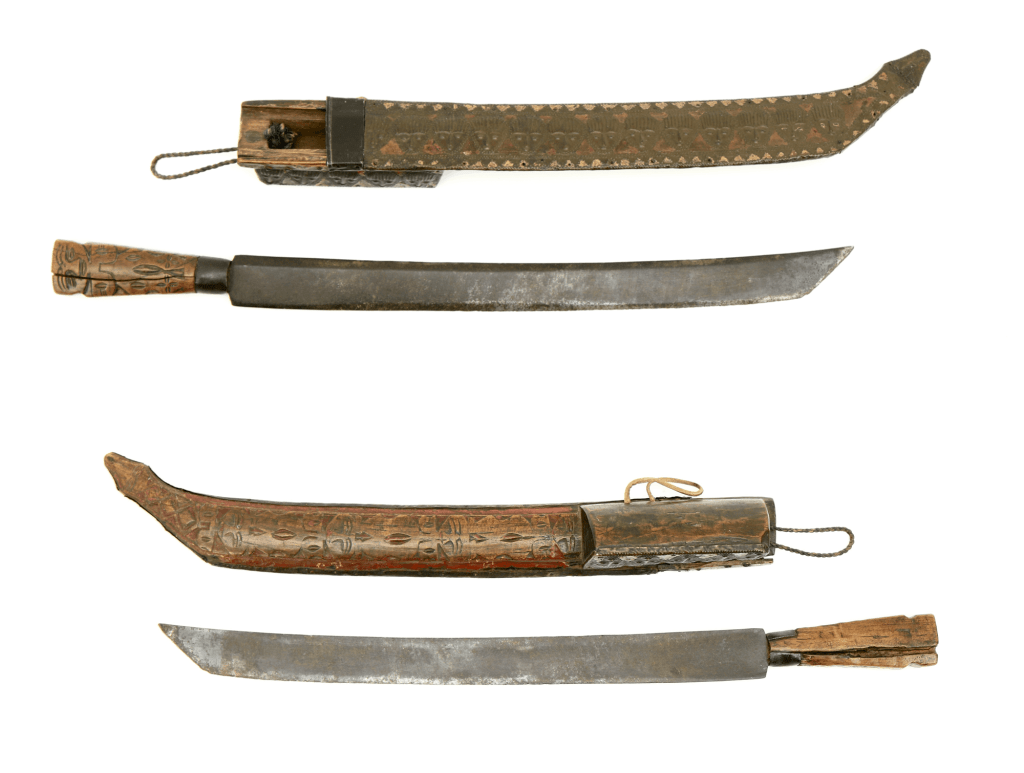

Another grouping that can be considered are the blades of the Puyuma, Paiwan, and Rukai, referred to as the Tjakit in the Paiwan language, the TaDaw in Puyuma/Pinuyumayan, and Lab/Lrabu/Rinadrug in Rukai.

The “Proto Tjakit“

While some early examples attributed to the Siraya bears a vague resemblance to Southern knives, there is another archaeological example that is closer to home. A knife in the collections of the National Museum of Prehistory in Taitung features a lot of characteristics found in later knives of Southeastern Taiwan. This particular example can likely be attributed to the descendants of the Beinan culture i near the Taitung plain, and shares some features of southern knives. It bears a cylindrical handle with a totemic depiction of a man at the pommel area, resembling later Puyuma blades, and a narrow blade profile similar to the later knives of the region. While this particular example is rather short, it is likely that it resembles the ancestral form of the knives of this region.

National Museum of Prehistory

Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma Warrior Cultures

Historically, the Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma had strong warrior cultures and forged powerful multiethnic tribal confederations/kingdoms which dominated much of the Pingtung peninsula. Each man was expected to undergo communal warrior training not unlike popular conception of the Spartan Agoge. The Puyuma have an institution for training young men known as the Palukkuwan which still exists to this day.

.

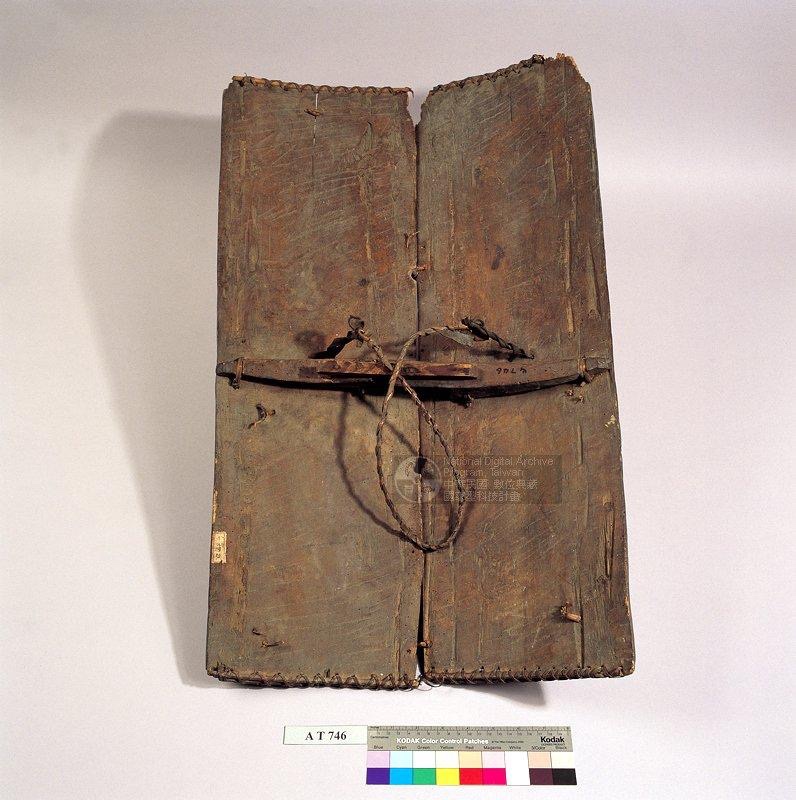

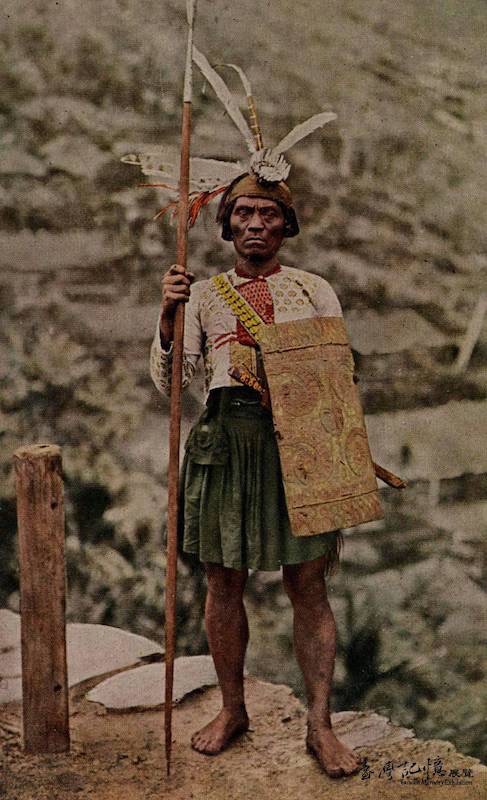

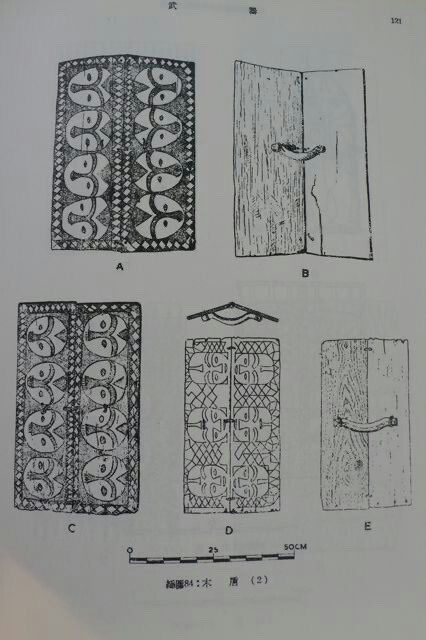

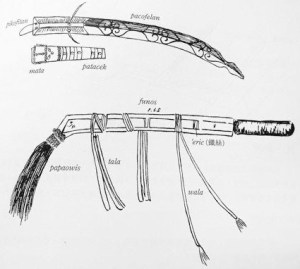

Warriors of the Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma were traditionally armed with spears, shields, swords, and occasionally bows, and later guns, with the primary weapons being the spear and the shield. The Southern Taiwanese shield is usually horizontally center gripped, rectangular, and made of 1 or 2 planks of wood. Many shields made of 2 planks often have a slight V cross section, with the junction between the 2 pieces secured by natural cordage woven through predrilled holes. The handle is similarly woven on. Theses shields varied in size, ranging from body sized to 1-2 feet in height, with a gradual shrinking in size as firearms became more prevalent. While these shields lost much of their battlefield use as time moved on, they were retained as ritual and cultural objects. However, it is important to keep in mind the role of the shield in the past when it comes to the swords of Southern Taiwan.

Knives of the Rukai, Paiwan, and Puyuma

These blades, like their cousins in the north, have an asymmetrical, chisel ground cross section, but are unique for featuring a well defined secondary bevel on one side of the blade, with the bevel closer to the spine for the Paiwan Tjakit and near the edge for Rukai Lrabu. In some Paiwan blades, a few are hollow ground on the flat side. These straight-single edged blades feature little to no distal taper, and thus the edges are nearly parallel until the tip, where the knife has an angled transition to the tip, similar to the kissaki on Japanese blades or the tip on Chinese blades. There is an interesting change in these Southern blades in that in earlier blades, the tip resembled Chinese blades, where the grind line meets the tip, providing a reinforced point, and the angle of the tip is usually around 45 degrees, whereas more modern blades feature a tip much like the Japanese kissaki, and are gently curved. It is possible that this change began with Japanese contact and later occupation of Taiwan, which the Paiwan were severely impacted by.

The Paiwan had 2 different types of knife, a utility knife/machete called the “sisavavuavua tjakit” and the ceremonial war sword known as the “sitjeqalaqala tjakit”. The utility Tjakit is usually less ornately decorated, and either features a socketed handle, or simple wooden handle. The Ceremonial war Tjakit exclusively has ornately decorated wooden handles.

Scholars Philip Tom and Sherrod V. Anderson have also been able to determine that these knives were constructed using qianggang/Sanmai construction, where softer, carbon poor steel is sandwiched around a carbon rich steel which also forms the edge, and heat treated with “considerable skill”. This has led them to posit a relationship with Chinese Blades from the Song Dynasty and earlier. Other possible influences on Southern Taiwanese blade design include shipwrecked sailors from Okinawa and Japan and various Filipino cultures that had traded with Taiwan until recently.

The Tjakit-type knife family is dominant in much of Southern Taiwan. While the dominant style of knife for Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma cultures, this type of blade was adopted by many neighboring peoples, including the Southern Amis, Bunun, Hla’alua/Saaroa, and the later arriving Taivoan and Makatao, though aspects such as scabbard and handle decoration was less widespread.

Fit and Finish of Southern Knives

Among the Paiwan and Rukai, ornamentation is of utmost importance. Unlike the rest of the tribes of Taiwan, the Southern Tribes had a strictly stratified social structure resembling a caste system, with distinct noble families. Considered one of the 3 treasures of Paiwan culture, along side glass bead making and pottery, the Paiwan Tjakit were crafted by the Pulima, an aristocratic caste serving as craftsmen for objects of prestige. The Tjakit, along side the other 2 treasures, were often given as high status gifts during special occasions like weddings, either as a dowry or bride price, or alliance forging. The handles and scabbards of Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma knives are ornately carved and painted, something generally absent from many other tribal knives in Taiwan. These decorations became more ornate depending on the social status of the owner.

The scabbards are usually made of Kleinhovia hospita or Taiwanese ebony(Diospyros philippinensis). These usually have a rectangular/trapezoidal design to conform with the shape of the knife, but the end is curved up like the bow of a ship. The protrusions at the end are often small and decorative, though some, in particular, those of the Puyuma, extend for a few inches. Like the scabbards of the north, the scabbards of the south often have wires stapled to the side to keep the blade secure, but unlike those of the north, these wires also serve a decorative role, twisted, coiled, and bent into patterns, with wires running nearly the entire length of the scabbard a common feature. Sometimes, copper/brass/bronze plate or wood panel is glued or stapled on, the surface of which also serves as a canvas for decoration.

Handle construction is similar to Northern knives, although with more emphasis on decoration. Socketed handles are usually decorated with a woven rattan grip. Wooden handle construction varies, as some knives feature a through tang with the tip hammered over the end(common in Chinese cutlery often used by Chinese settlers throughout Taiwan) or a tang that is hammered into a piece of wood and sealed with adhesive. The more prestigious wooden handles are often fitted with a ferrule, and have a cylindrical, rectangular, or flattened octagonal cross section, sometimes a combination of the above. Each surface was carved, painted, and inlaid with precious metals, stones, mother of pearl, and other decorative elements. It is not uncommon to find Chinese, Japanese, or even American coins glued or embedded onto the scabbard, sometimes even used as a small disc guard, though the guard was far from a universal feature. The flattened octagonal handle in particular was a common feature of Rukai knives, though since the Japanese occupation, the handle was adopted by neighboring Paiwan villages, and had since become the dominant aesthetic for Southern Taiwanese knives.

The emphasis on decoration is likely linked to the affinity of Rukai and Paiwan tribesmen for wood carving, with the handle and scabbard serving as a surface for displaying craftsmanship. Motifs/totems are hammered in metal and carved into the wood, common ones being faces, often representing ancestors, and the “hundred pace pit viper”(Deinagkistrodon), an animal of significant importance to the Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma.

Photo and description Courtesy of Peter Dekker of Mandarin Mansion

On the upper portion of many Paiwan scabbards, there is often a box or protrusion. These are roughly trapezoidal/rectangular, and are hollowed out for storage of materials such as tinder. The knife, when in the scabbard, effectively serves as a “lid” for the box. This either facilitates or dictates the way the Tjakit is worn, in which the side of the box props up the scabbard in such a way that the blade faces up. There are roughly 2 ways of tying the Tjakit to the waist. A series of 4 holes are often found on either the forward and backward walls of the box, or on the face of the scabbard itself when the box is absent. A cord is usually strung through each set of 2 holes and tied, forming 2 loops for a belt, which is then tied around the waist. The more ceremonial way of wearing the Tjakit would be to tie or wrap an ornate braided cord of ramie around the scabbard(usually right behind the box), then used the rest of the cord as a belt. In absent of the box, some knives have a small wooden protrusion resembling a strip, and many scabbards, particularly those of the Rukai and Puyuma, have no such protrusion.

Knives of the Amis/Pangcah

In terms of material culture, the Pangcah absorbed much from their neighboring cultures, such as the Truku, Sakizaya, Kavalan, Pinuyumayan(Puyuma), and Paiwan. As such, knives of the Pangcah, called Funos/Vunos, varied greatly depending on region, and like many other things in Taiwan, there is a North South continuum, with Northern knives resembling Atayalic Laraw and Southern knives resembling the Tjakit.